This is part of a series on the Global Goals for Sustainable Development, in collaboration with the Stockholm Resilience Centre. This article focuses on goal 1 – End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

The first goal in the soon-to-be minted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is quite a curtain-raiser: it calls on us to work together to end poverty in all its forms, everywhere. This intention to eradicate, not just reduce poverty, represents a major leap forward in terms of ambition compared with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and is echoed in the commitment to “leave no one behind”.

But when I go to New York to join those ushering in these new goals I will be wondering whether we are prepared to do what it takes to make such a goal come true.

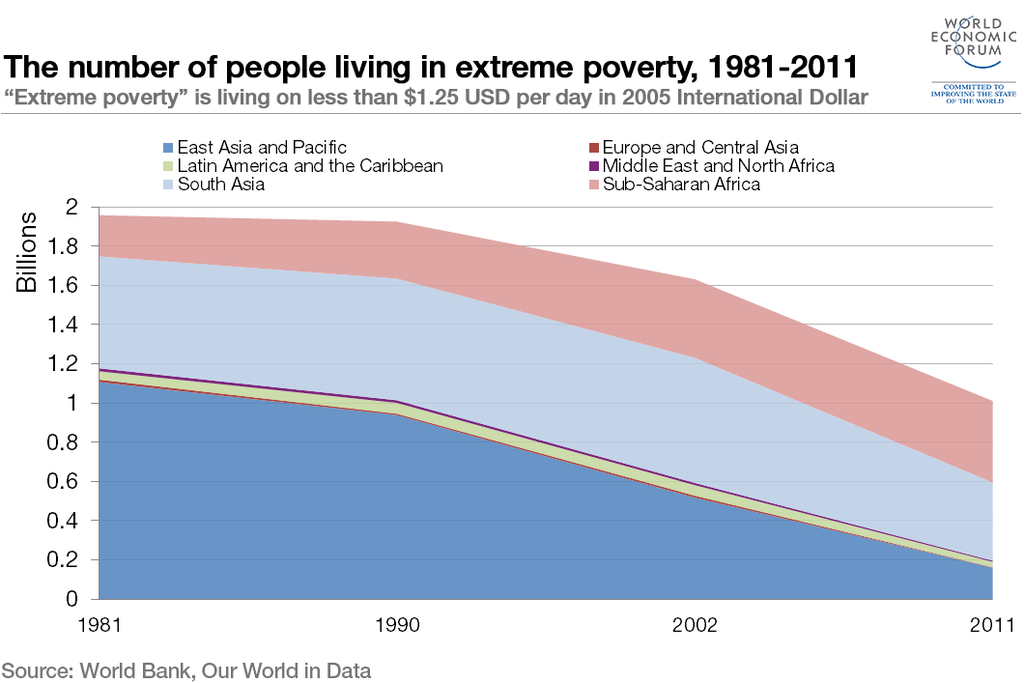

The predecessor to this goal, MDG 1, asked us to halve extreme poverty rates (at 1990 levels) by 2015. We met the goal five years early, but this achievement was marred by stark regional differences. In my own continent of Africa, almost one out of every two people still lives in extreme poverty. This is more than four times greater than the world average.

We are a long way from eradicating poverty and leaving no one behind. What’s more, we have been busy making our task harder: globally we face the growing challenges presented by extreme economic inequality and climate change – both of which seriously undermine the fight against poverty.

I still firmly believe that we can eradicate poverty by 2030, but that will require us to do things very differently from the MDG period:

Implementation requires us to be political

Delivering these goals is not a technocratic exercise. Success will require us to challenge power and vested interests. Are governments – rich and poor – prepared to take on vested interests: those who profit from maintaining global emissions or those elites who get ahead in an unequal world? Will civil society have the ability to combat these vested interests and hold governments to account?

If we are asking poor governments to take on more responsibility, then power and control of resources must shift too

Poor governments will have a responsibility to change policy priorities and spending allocations, and look to their own domestic resource mobilization. But we have to watch out for a certain hypocrisy here where rich governments are happy to share responsibility but not to share the power and control of resources that poor countries will need. A case in point is the need to reform global tax rules to prevent revenues of about $100bn each year being lost to developing country treasuries. We made a disappointing start at the Financing for Development summit in Addis with the failure to agree a global tax body to help ensure fair global tax rules. We must do better.

Private sector delivery and financing is not a magic bullet

Private finance is needed and the willingness of companies to engage in the SDGs is welcome. But, so far, there are inadequate checks and balances to ensure public-private projects work in the public interest, safeguard people’s rights, or best serve local communities. The dangers of going ahead without such safeguards are evidenced in Oxfam’s investigation into the Queen Mamohato Memorial Hospital in Lesotho, which was built under a public-private partnership. The Ministry of Health is locked into an 18-year contract that already consumes more than half of its health budget. This is a dangerous diversion of scarce public funds from primary healthcare services in rural areas, where three-quarters of the population live.

If these are the big structural changes that I think will make a difference, what about some signs that we are on the right track? In the next 12 months we need to work to ensure that:

The UN climate change summit delivers

Climate change and extreme economic inequality will reverse, in no time, decades of hard-won progress in the fight against poverty. A strong agreement in Paris is a vital step on the road to zero hunger and to achieving the global goals.

All governments, rich and poor, make national implementation plans

These should be clear and binding – with targets broken down in three- to five-year milestones. They should ensure the full participation of citizens and civil society in the delivery of these goals, and ensure that participatory monitoring systems are put in place to enable citizens to hold governments to account. Remember, the richer you are as a country, the more international responsibility you bear as well as responsibility to your own populations.

Redistribution is no longer a taboo

Governments must make the fight against extreme economic inequality central to their national SDGs strategies – it is a structural cause of so many issues the other goals aim to tackle. A commitment to progressive policies that redistribute resources to close the extreme inequality gap as well as eradicate poverty would also signal a clear and permanent goodbye to the kinds of policies that have allowed such a growing gap between rich and poor to develop.

None of this is easy: It involves taking on the power of the 1% in favour of the interests of the most poor and most marginalized. I am looking forward to welcoming these new goals later this month. But now the real work starts. –Winnie Byanyima, https://agenda.weforum.org/2015/09/how-can-we-eradicate-poverty-by-2030/